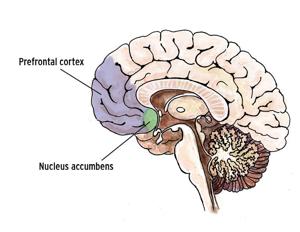

Long-term crystal meth use damages the prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain that controls complex cognition while raising dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens, research shows.

-

by Ryan Thorne

Since 2010, 22 people have been convicted for felony crystal methamphetamine trafficking, distribution or possession in the Wood River Valley. In addition, a handful of Blaine County jail inmates and Wood River Valley residents are currently awaiting court appearances for various methamphetamine charges.

“Unfortunately, it still is a very accessible drug in the valley,” Blaine County Sheriff Gene Ramsey said. “The Idaho Meth Project has been on an educational path for several years, but we still see it fairly often.”

While other drugs such as cocaine and marijuana often originate in Mexico or South America, Ramsey said he believes the crystal methamphetamine that is sold in Blaine County comes from the Boise area.

“We haven’t seen it here, but in the Treasure Valley, people will rent a hotel room and make it in the bathtub,” he said. “I honestly don’t believe that much of it is coming from Mexico—they have their own trade and I think it is being manufactured right here in Idaho or in Oregon.”

Ramsey said that when he visited Tennessee recently, crystal meth seemed to be a problem there, as well.

“People were transporting it right on the interstate,” he said.

Combating the problem

Idaho Meth Project Executive Director Adrean Cavener said the nonprofit organization’s goal is to prevent methamphetamine use among adolescents and teens through media campaigns and community outreach.

“We do media school presentations, safe and drug-free activities for teens that include graduation parties for alternative high schools,” she said. “They don’t have parent teacher associations and booster clubs.”

Cavener said the organization has presented at Wood River High School assemblies for the past three years. She said the assemblies usually involve a presentation showing the negative effects of the drug on the human body, and former addicts share their stories regarding meth addiction.

“We reach out to Idaho schools every year and they also reach out to us,” she said. “A lot of nonprofits say they are an Idaho organization but are just based out of places like Boise. We are truly all over the state.”

Idaho Meth Project commercials illustrate the horrors of crystal meth addiction, showing scenes in which teenage girls sell their scab-covered bodies to seedy, older dealers in exchange for the drug.

“What we promised teens is that we will never sensationalize the drug world, but we’re not going to sugar-coat it either,” she said. “I think that teenagers have a finely tuned radar, so being candid is what we are about.”

According to data compiled by the Idaho Meth Project, 80 percent of the methamphetamine in Idaho comes from Mexico. In 2013, more than half of Idaho inmates attributed their incarceration to meth addiction.

“Because we are importing meth, it is cheaper, more available and in higher purities than even five years ago,” Cavener said.

History and science behind meth

Meth use may have played a large role in the shaping of the modern world. In his recently published book, “Der Totalle Rush” (“The Total Rush”), German writer Norman Ohler alleges that Nazi air pilots and ground troops took a drug called Pervitin, essentially methamphetamine in a pill form, to stay alert and awake during combat operations. Ohler’s book claims the drug was sold over the counter in the first half of the 20th century in pharmacies across Europe and was eventually handed out to Nazi soldiers on the front lines of World War II.

According to the Foundation for a Drug Free World, a nonprofit organization that distributes drug information in pamphlets worldwide, large doses of methamphetamine were given to Japanese Kamikaze pilots before missions in the South Pacific during World War II. Shortly after the end of the war, large supplies previously stored for military use were made available to the public, and abuse by injection reached epidemic proportions in Japan. In the U.S. during the 1950s, methamphetamine was prescribed as an antidepressant and diet aid, but was generally outlawed in the 1970s. Motorcycle gangs distributed crystal meth in the ’70s and ’80s to consumers too poor to afford cocaine until Mexican cartels began to dominate meth trafficking and production in the ’90s.

Since the Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act of 2005 was enacted by Congress, American consumers are limited to the amount of nonprescription cold and allergy products they can purchase containing pseudoephedrine, ephedrine or phenylpropanolamine. Those substances are used to make crystal methamphetamine, and buyers are required to show identification and sign a log book when buying the products.

However, American doctors can still prescribe a form of meth, methamphetamine hydrochloride, for children and adults with attention-deficit hyperactive disorder and obesity.

Dr. Petros Levounis, chair of the Department of Psychiatry at Rutgers Medical School in New Jersey, said crystal methamphetamine is a far stronger than its pill cousins. He said it raises the dopamine levels of the nucleus accumbens, located directly behind the prefrontal cortex in the brain.

“That is the center of the brain that is responsible for pleasure and reward,” Levounis said. “Most people hypothesize that crystal methamphetamine, in the way that it is smoked and used, probably jumps the dopamine level at 4,000 or more [percent] above its baseline.”

Levounis said an average dopamine baseline stands at 100 percent, sex raises dopamine levels in the brain to 200 percent and cocaine use raises an individual’s dopamine levels to 350 percent.

“So, in a sense, crystal methamphetamine is the nuclear weapon in the brain, contrasted to conventional weapons of alcohol, cocaine and marijuana,” he said.

Crystal meth hijacks the pleasure reward pathways of the brain, Levounis said, making the drug the most important thing in a user’s life.

“At the same time, it reduces the rational parts, specifically the cognitive centers found more in the frontal part of the brain,” he said. “That combination makes a person severely addicted to crystal methamphetamine.”

Levounis said meth users also experience a direct toxic effect on the neurons in the brain.

“The toxic effect destroys parts of the neurons that do regenerate, but when they regenerate, they do so in a much more chaotic fashion,” he said. “That’s why we see that people who have abused crystal methamphetamine for a long time are quite likely to suffer from some kind of sequelae—loss of concentration, loss of short- and long-term memory and things of that sort.

“In general, we are amazed at how forgiving the body is to abuse of drugs. However, with crystal methamphetamine, that particular toxic effect seems to be irreversible.”

Not only will crystal meth cause long-term brain damage, Levounis said, but the physical effects of the drug’s use are also apparent in addicts. Many suffer from skin abscesses and poor dentition.

He said there exists effective medication for tobacco and opioid use, but there is no current medication that can help meth users kick their habit.

“It has been the Holy Grail of my field to find something but we haven’t been able to,” Levounis said. “However, we do have very successful psychotherapies and psychosocial interventions for crystal methamphetamine addiction.”

Levounis said he has noticed that when a drug becomes popular in New York, it generally spreads to the West Coast, and vice versa. But with crystal methamphetamine, that wasn’t the case.

“It became huge in the West and Southwest but not the New York area,” he said.

Meth is used on the East Coast primarily by gay men who consume the drug in conjunction with sex to enhance their experience, Levounis said. He said that when he spoke at a conference in Oregon a couple of years ago, nobody on the West Coast had heard of the drug primarily being used that way.

“On the West Coast, and I assume Idaho as well, it’s not particularly a sexual drug, it’s more of a recreational drug,” he said. “It has a very different profile and suits men and women, gay and straight.”